-

ICE activity/raids

Another life destroyed for no reason. I am glad the sheriff said what they did regarding the man and his family being productive members of the community. Much more than I'd expect out of a rural Texas sheriff's office. Also, crazy that I am seeing the tiny town of Froid on here. I know people from Froid and have spent a good amount of time around there.

-

Elon Musk: Nazi traitor piece of shit [Confirmed]

I decided to check out Grokipedia, just to find out what it did with a Wikipedia article I researched and wrote on Nicholas Fagan, an early Texas settler. It originally went through the internal Wikipedia review process before being released to the public. Grokipedia: 1) Copied a lot, like the general storyline 2) Used almost entirely non-peer reviewed or published sources. Grok has three published sources (but uses website links only), and one of those sources has limited info on the subject. (Wikipedia has 17 peer reviewed and/or published sources for reference). Grok has 8 sources that are links to random websites. 3) Contains hallucinated "facts." Examples: claims location of Spanish shipwreck was on his land (it was not), and many other small, incorrect details. In one part the boat that he took to Copano from New Orleans' name is "Panoma," next it is "Pomona". For the most part, I can tell where the background story is coming from, but the specific "facts" are literally made up or extrapolating the baseline facts. 4) Friend's with Mexicans, DEEMPHASIZED. Lessened the relationship with Nicholas' Mexican neighbor, Carlos de la Garza: friend ==> former acquaintance. They lived and fought together on the frontier for over 20 years. His neighbor, Carlos, took care of him while establishing a homestead in Texas, and literally saved his life twice, but he's just a former acquaintance... 5) Maybe I'm reading too much into it, but it seems that religion is EMPHASIZED. Focus on Nicholas' faith enough to make it a main feature of the article. In the future the truth is going to be hard to come by with AI crawling the internet and training on extrapolated "facts" If anyone cares to read: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Fagan and Grokipedia - Nicholas Fagan Nicholas Fagan Nicholas Fagan (c. 1785 – August 30, 1852) was an Irish immigrant who became a pioneering settler, blacksmith, and rancher in Refugio County, Texas, playing a role in the Texas Revolution as a fighter under Philip Dimmitt and James Fannin.[1][2] Born in County Westmeath, Ireland, he emigrated in 1816, residing in New Orleans where he married Catherine Hanselman Balsch, before reaching Texas in 1829 and receiving a land grant along the San Antonio River finalized in 1834.[1] During the Revolution, Fagan joined the garrison at La Bahía, raised the "bloody arm" Goliad flag, and was captured at the Battle of Coleto Creek but escaped execution in the Goliad Massacre through intervention by a Mexican acquaintance, Carlos de la Garza.[1] Post-independence, he expanded his ranching operations, fathered eleven children across two marriages, and was remembered for his Catholic faith, generosity, and establishment of a family cemetery, earning recognition as a Republic of Texas hero.[1] Early Life and Origins Birth and Irish Background Nicholas Fagan was born circa 1785 in County Westmeath, Ireland, as indicated by the 1850 U.S. Census listing his age as 65 at the time of enumeration.[1] His parents were James Fagan and Annie, the latter being a first cousin to Lord Edward Pakenham, linking the family to Irish gentry with British military ties; Pakenham, a first cousin once removed to Nicholas, was killed at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.[3] [1]Raised in a Catholic family amid Ireland's penal laws, which imposed severe restrictions on Catholic practices and property rights under British rule, Fagan experienced the era's religious persecution that prompted many Irish Catholics to emigrate.[3] Family tradition recounts that at age fifteen, Fagan and his cousin Edward Pakenham attempted to run away from home in Dublin to enlist as sailors on a British battleship, but after facing hardship and rejection for lodging due to lack of funds, they were persuaded by a sympathetic woman to return home; Pakenham later pursued a military career in the British Army, while Fagan remained in Ireland.[3]These accounts, drawn from family oral histories and 19th-century memoirs, underscore Fagan's roots in Westmeath's rural Catholic communities, where economic hardship and religious oppression shaped early decisions, including his eventual marriage to Kate Connelly of County Meath before departing Ireland.[3] Immigration to America and Path to Texas Nicholas Fagan was born circa 1785 in County Westmeath, Ireland, to parents James Fagan and Annie, the latter a first cousin of Lord Pakenham.[1] [3] Fagan emigrated from Ireland in 1816 amid penal laws restricting Catholic practices, arriving in New York City with his first wife, Kate Connelly, and their daughter Annie (born 1814).[3]The family resided in New York for four years before relocating southward through Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, where they stayed three years, driven by dissatisfaction with the climate and distance from Catholic churches.[3] They then descended the Mississippi River via flatboat to New Orleans, where a yellow fever epidemic claimed Kate Connelly's life; Fagan subsequently married widow Catherine Hanselman-Balch there, forming a household including children Annie, John, and Mary.[3]In 1829, Fagan, his second wife Catherine, and family sailed from New Orleans aboard the Panoma under Captain Prietta, a Spaniard with a permit to land at Copano, arriving February 28.[3] From Copano, they proceeded overland by ox cart—accompanied by the McDonough family—to a site on the San Antonio River's south bank in present-day Refugio County, securing a league-and-labor grant in James Power's colony, which formalized in 1834.[3] [1] This path positioned Fagan among early Irish settlers in Mexican Texas, navigating storms and livestock losses en route.[3] Pioneering in Mexican Texas Settlement in Power's Colony Nicholas Fagan arrived in Mexican Texas on February 28, 1829, disembarking at the port of Copano aboard the schooner Pomona with his second wife, Catherine Hanselman-Balch, children from his first marriage, and household possessions. Traveling inland with the McDonnough family, he selected a settlement site about twenty miles above Copano on the south bank of the San Antonio River, in an area then part of the La Bahía municipality and later incorporated into the Power and Hewetson Colony. The group endured a severe blue norther during their overland journey but received assistance from the local Hernandez family, who provided shelter until Fagan could erect a rudimentary log cabin using timber felled from the riverbanks.[3][4]Fagan formalized his claim through a land grant of 9,537 acres issued by empresario James Power, though records indicate official documentation dated August 4, 1834, after five years of prior occupancy.[5] He enhanced the initial dwelling with lumber salvaged from a wrecked brigantine nearby, which also inspired the naming of adjacent Burgantine Creek. The isolated homestead, situated in a sparsely populated frontier amid four indigenous groups—Lipan Apaches, Tonkawa, Comanche, and Karankawa—benefited from cooperative relations with neighboring Mexican ranchers such as the De la Garzas and Hernandez families. Fagan employed Copano Indians for tasks like crop harvesting and cattle tending, compensating them with whiskey, fostering a period of relative peace and self-sufficiency before the disruptions of the Texas Revolution.[3] Economic and Community Roles as Blacksmith and Rancher Upon arriving in Power and Hewetson's Colony in 1829, Nicholas Fagan established himself as a blacksmith, leveraging skills and tools he had brought from Ireland to provide essential metalwork services to fellow settlers in the Refugio area.[3] His forge supported the nascent community's infrastructure needs, including repairs and fabrications drawn from local resources such as iron salvaged from a wrecked brigantine on his property, which he repurposed for constructing a two-story residence featuring an upper-story chapel used for Mass by itinerant priests serving settlers between Victoria and Refugio.[3]As a rancher, Fagan received a land grant of 9,537 acres from empresario James Power, on which he cultivated corn and raised cattle, adapting to the region's challenges like Indian depredations by initially sourcing grain from the Caney Bottoms and grinding it with millstones he imported from Ireland.[5][3] He further contributed economically by erecting a mill on his holdings, though he declined the three leagues of additional land offered as a Mexican government subsidy for such improvements.[3] These activities not only sustained his household but also bolstered the colony's self-sufficiency amid sparse imports, with wheat still drawn from Mexico while local corn production expanded among San Antonio River settlers including Fagan.[3]Fagan's dual roles fostered community cohesion in the isolated frontier setting, where his blacksmithing addressed practical shortages and his ranching output aided collective resilience against environmental and indigenous threats.[3] His property evolved into a core ranching operation focused on cattle, portions of which persist today as historic resources emphasizing livestock as the primary economic product in Refugio County.[5] Military Service in the Texas Revolution Early Involvement with Philip Dimmitt In October 1835, shortly after the outbreak of the Texas Revolution, Nicholas Fagan joined Philip Dimmitt's volunteer company at the Presidio La Bahía (Goliad), reinforcing the garrison following Dimmitt's capture of the fort from Mexican forces on October 10.[1] Fagan, having sent his family to safety in Louisiana, served as quartermaster in Dimmitt's command, managing supplies and logistics for the Texian defenders amid escalating tensions with Mexican authorities. Fagan's involvement deepened during key early revolutionary events at Goliad. On December 20, 1835, after Dimmitt's men issued the Goliad Declaration of Independence—the first formal Texian proclamation of separation from Mexico—Fagan cut a sycamore pole from nearby woods to serve as a staff for raising Dimmitt's newly designed flag, featuring a severed arm wielding a bloody sword on a blood-red field, symbolizing defiance against Mexican rule.[6] This act marked one of the earliest public displays of Texian independence, with Fagan personally hoisting the banner over La Bahía in celebration, as recounted in participant memoirs including his own recollections.[7]His quartermaster duties under Dimmitt positioned Fagan to support operations like scouting and fortification efforts, contributing to the garrison's readiness before Dimmitt's departure in January 1836. These early actions highlighted Fagan's logistical acumen and commitment, though records note occasional command tensions, including Dimmitt's volatile leadership style, which Fagan navigated while maintaining focus on revolutionary objectives. Service under James Fannin In early 1836, following Captain Philip Dimmitt's relinquishment of command at Presidio La Bahía (Goliad), Nicholas Fagan enlisted under Colonel James Walker Fannin, who took charge of the Texas volunteer forces there. Fagan's prior experience in Dimmitt's company facilitated his integration into Fannin's garrison, where he focused on logistical support amid preparations to counter advancing Mexican troops under General José de Urrea. He donated his entire corn crop, several hundred head of cattle, and transport carts to sustain Fannin's approximately 400-man command, contributions later affirmed in testimony by associate William P. Ehrenburg.[3]On March 11, 1836, Fannin dispatched Captain Amon B. King with a small detachment to Refugio to evacuate Anglo and Mexican families fleeing Urrea's forces during the "Runaway Scrape." Fagan volunteered among roughly 28 men in King's party, leveraging his local knowledge as a Refugio County settler to aid the mission. The group clashed with Mexican cavalry near the Aransas River, providing covering fire to protect refugees before withdrawing to the Nuestra Señora del Refugio Mission on March 14.[8]During ensuing skirmishes at the mission, Fagan participated in defensive actions against Urrea's troops, which forced King's surrender on March 15. While scouting afterward, Fagan encountered a Mexican ranchero unit led by Captain Carlos de la Garza, a former acquaintance from colonial interactions; de la Garza accepted his parole and released him, enabling Fagan to evade execution and return to Goliad to rejoin Fannin's main force by mid-March. This episode underscored Fagan's tactical adaptability in detached operations under Fannin's strategic oversight.[3][8] Capture at the Battle of Coleto and Goliad Massacre Survival Fagan, serving in Colonel James Walker Fannin's army as a blacksmith, joined the retreat from Goliad toward Victoria on March 19, 1836, amid the escalating Texas Revolution. Mexican forces under General José de Urrea, numbering around 1,500, ambushed Fannin's roughly 400 men at Coleto Creek, where the Texans formed a defensive square but suffered from inadequate ammunition, water shortages, and no artillery support. After heavy fighting, Fannin surrendered unconditionally on March 20, 1836, with approximately 445 prisoners taken, including Fagan.[3]The captives, denied parole despite initial assurances, were marched approximately 27 miles back to Presidio La Bahía at Goliad under harsh conditions, arriving by March 24. There, they joined other Texan prisoners, including survivors from earlier engagements like Refugio, where Fagan had previously been spared execution through local Mexican intervention. General Urrea, adhering loosely to Santa Anna's no-quarter policy while selectively paroling some, could not override orders for mass execution. On Palm Sunday, March 27, 1836, around 342 Texans, including Fannin, were divided into groups and shot or bayoneted outside the presidio in the Goliad Massacre, with bodies burned in piles. Fagan survived, likely due to his utility as Fannin's blacksmith and preexisting ties to Mexican colonists in the area, such as Captain Carlos de la Garza, who had paroled him at Refugio and reportedly arranged for Fagan to be removed for ironwork the day before, hiding him during the killings. Historical accounts, including family traditions preserved in Fagan's scrapbook, emphasize these personal connections over mere skill, noting he was spared twice—first at Refugio in mid-March and again at Goliad—amid Urrea's documented reluctance to execute artisans and non-combatants.[3] Following the massacre, Fagan evaded recapture and contributed to Texan intelligence efforts before the San Jacinto victory in April.[3] Post-Revolution Life and Leadership Ranching Expansion and Local Influence Following his survival of the Goliad Massacre, Nicholas Fagan returned to his ranch along the lower San Antonio River in Refugio County, where he resumed cattle ranching on the property originally granted as a league and a labor of land by empresario James Power in 1829.[3] He expanded the ranch's homestead by salvaging lumber and iron from a wrecked brigantine discovered on his property—now known as Burgantine Creek—to construct a sturdy two-story house atop an initial log structure, enhancing its durability amid ongoing frontier threats.[3] Cattle remained the principal focus of operations, though herds faced repeated depredations from Mexican raiders, Native American groups, and white rustlers through the 1850s, necessitating vigilant defense to sustain the enterprise.[3]Fagan's ranch evolved into a vital economic and communal anchor, serving as a base for regional cattle activities while providing refuge during crises, such as the October 1, 1850, incident when settler Eve Thomas, wounded in an Indian raid, received care there from Fagan's wife and Dr. R.W. Wellington.[3] By maintaining operations despite losses, Fagan's holdings contributed to the broader Irish settler economy in the San Antonio River district, influencing patterns of land use and livestock management in northern Refugio County.[3]In local affairs, Fagan exerted significant influence as a de facto leader, enlisting in Power’s and Cameron’s Spy Company (1836–1838) and a ranger unit under Captain J.T. Tomlinson (1836–1839) to counter raids, alongside neighbors like Thomas O’Connor and Carlos de la Garza.[3] His ranch hosted a posse in 1851 or 1852, including sons John and William Fagan, John Hynes, and O’Connor, which repelled a Karankawa band, bolstering settler security.[3] Fagan's stature peaked in September 1841, when, after a Mexican raid led by Ortegon devastated Refugio, he organized ox-cart relief with food, clothing, and blankets, relocating destitute families to river ranches; many resided with the Fagans until ransomed years later, earning him the moniker "Savior of Refugio" and a gift of the Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Concepción mission bell from grateful citizens.[3]The ranch also functioned as a religious and social hub, with Father Jean Marie Odin (later bishop) celebrating Mass in its private chapel from 1839 to 1840, drawing settlers from Victoria to the bay for sacraments amid sparse clergy.[3] Fagan's alliances with Mexican ranchers like de la Garza, who had aided his survival at Goliad, fostered cross-cultural cooperation, while his consistent generosity—rooted in Catholic principles—solidified his role as a stabilizing force until his death at the ranch on August 30, 1852.[3][1] Encounters with Native American Conflicts Following the Texas Revolution, the Refugio County region, including areas near Nicholas Fagan's ranch on the San Antonio River, experienced renewed Native American raids from approximately 1840 to 1855, primarily by Karankawa and Comanche groups emboldened by prior Mexican incursions.[3] These depredations involved theft of livestock, attacks on settlers, murders, and captures of women and children, prompting local posses of Anglo and Mexican ranchers to pursue and confront the raiders.[3] Fagan, as a prominent rancher and community leader, actively participated in these responses, reflecting the frontier defense typical of Irish settlers in the area.[3]A notable incident occurred in March 1842 near Fagan's ranch, known as the Gilliland Massacre, when Comanche raiders attacked the home of William Johnstone Gilliland and Mary Barbour Gilliland on the west side of the San Antonio River.[9] The couple was killed in their yard, and their children—Rebecca Jane, about 12, and William McCalla, about 9—were taken captive; the attackers also raided nearby ranches, including that of Philip Howard.[9][3] The night prior, young Fanny Fagan had been invited to stay with the Gillilands but was kept home by her mother, sparing her from the assault.[3] Local settlers, including Fagan, raised the alarm and pursued the Comanches; in the ensuing fight that afternoon, the raiders, outnumbered but unwilling to carry the captives further, abandoned William unharmed and struck Rebecca, presuming her dead.[3] Fagan, alongside Carlos de la Garza and Thomas O'Connor, searched the area and located the children alive after hearing Fagan's voice; they were transported to Carlos Ranch for initial care, then to Victoria under O'Connor's guardianship, where the children recovered.[3]In 1844, Karankawa raiders targeted Kemper's Bluff on the lower Guadalupe River, a few miles from Fagan's property, killing Captain John Frederick Kemper with an arrow.[3] Fagan joined a posse comprising Irish settlers from the San Antonio River settlements, Mexicans from Carlos Ranch, and men from Victoria and Refugio; the group chased the Karankawas downriver toward the bay, engaging them in combat.[3]A Comanche raid on October 1, 1850, struck the Salt Creek Ranch of Jacob Thomas near Fagan's holdings, capturing two girls, Sarah (11) and Eve (15), while they herded cows.[3] Eve survived wounds, climbed a tree for safety, and was rescued the next morning by her brother John Thomas and John Fox; she was taken to Fagan's ranch, where Mrs. Fagan nursed her and Dr. Royal W. Wellington treated her injuries until she could return home.[3]The final major confrontation involving Fagan came in 1851 or 1852, when Karankawa remnants reappeared along the lower Guadalupe and Hynes Bay.[3] A posse of about 20 men, including Fagan, his sons William and John, Thomas O'Connor, Dr. Wellington, and Carlos de la Garza, assembled at Fagan's ranch under John Hynes's leadership and surprised the group, killing several after a fierce exchange that wounded some settlers; the survivors fled, effectively ending Karankawa threats in Refugio County.[3] These encounters underscored Fagan's role in communal defense amid persistent frontier violence.[3] Personal Life, Faith, and Legacy Family, Catholic Devotion, and Generosity Nicholas Fagan married his first wife, Kate Connelly, from County Meath, Ireland, around 1813–1815; she died during a yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans shortly after the family's arrival there.[3] With Connelly, Fagan had three children: Annie (born 1814 or 1816 in Ireland), John, and Mary.[3] [1] He remarried Catherine Hanselman Balch, a Lutheran widow, on January 17, 1824, in New Orleans; she later converted to Catholicism and raised their children in the faith, serving as a devoted wife, mother, and stepmother.[3] [1] Fagan and Balch had eight children, including Peter (the youngest son), Fanny, Thomas, and Margaret, several of whom died young.[3] Annie Fagan married Peter Teal in January 1833 at her father's Refugio County home, with the ceremony officiated by a Mexican priest.[10] [3]Fagan's Catholic devotion stemmed from his Irish roots, where English penal laws restricted practice of the faith, prompting his emigration in search of religious freedom.[3] In Refugio County, he constructed a two-story ranch house with the upper level dedicated as a chapel, including an altar, confessional, and priest's quarters, which hosted Masses for local settlers served by priests such as Padres Valdez, Garcia, and Bishop Odin (who visited in 1839–1840).[3] [10] A 1767 mission bell from Nuestra Señora de la Refugio Mission hung on the chapel's gallery to call the faithful to services; Fagan later willed it to his grandson Dennis O’Connor, who placed it in St. Dennis Church.[3] His commitment extended to physically defending the chapel, as when he assaulted a thief desecrating the altar tabernacle, hurling the intruder down the stairs—an incident recounted by son Peter.[3] Fagan's mother had similarly prioritized Catholic communities during earlier migrations, underscoring the family's enduring faith.[10]Fagan was renowned for his generosity and charity, exemplified during the Texas Revolution when he donated his corn crop and several hundred cattle to Colonel James Fannin's army without compensation, alongside providing supply carts.[3] In September 1841, following a devastating Mexican raid on Refugio that left families destitute, Fagan and neighbors loaded ox-carts with food, clothing, and blankets to evacuate and shelter women and children at safer ranches, including his own; for this, Refugio citizens dubbed him the "Savior of Refugio" and gifted him the Refugio Mission bell.[3] He further demonstrated aid in 1842 by helping rescue and care for orphaned Gilliland children after an Indian attack, and in 1850 by nursing injured settler Eve Thomas at his ranch following another raid.[3] Fagan enclosed a family graveyard to protect graves, where he was buried upon his death on August 30, 1852.[3] Death, Burial, and Historical Commemoration Nicholas Fagan died on August 30, 1852, at his ranch in Refugio County, Texas, at approximately age 67.[1][3]Fagan was interred in the Fagan family cemetery on his ranch property, located about ten miles west of Tivoli and six miles northwest of Tivoli north of State Highway 239.[11][5] He had personally enclosed the site to protect the graves of family members and others, reflecting his commitment to preserving burial grounds amid frontier conditions.[3] The cemetery, now known as the Nicholas Fagan Memorial Cemetery, remains on private land and contains marked graves from the period, though it is not open to the public.[11][5]Fagan's historical commemoration centers on his survival of the Goliad Massacre in 1836, where he was spared execution due to intercession by local Mexican allies, and his broader role as an Irish-born pioneer, blacksmith, rancher, and Texas Revolution participant.[3] Accounts portray him as a generous Catholic faithful who aided neighbors and embodied early settler resilience, as detailed in local histories like "Nicholas Fagan: A Texas Patriot."[3] The Texas Historical Commission has surveyed and documented the memorial cemetery as a site of early Refugio County heritage, underscoring Fagan's lasting local influence without formal state markers noted in primary records.[5] His legacy persists in genealogical and patriotic narratives emphasizing self-reliance and community service in post-independence Texas.[1][3] References https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/85251510/nicholas-fagan https://www.jstor.org/stable/40732050 https://scrankin.com/archives/nicholas-fagan-texas-patriot/ http://www.stxmaps.com/go/texas-historical-marker-nicholas-fagan.html https://www.thc.texas.gov/public/upload/preserve/harvey/HarveySurvey/FINAL_July-2023/FINAL%20Refugio%20County%20Historic%20Resources%20Survey%20Report_2023-07-17.pdf http://www.sonsofdewittcolony.org/adp/history/republic/flags/dimmits.html https://texasflagpark.net/texas-flags/goliad-flag-severed-arm-bloody-sword-1836/ http://www.sonsofdewittcolony.org/goliadmen.htm http://sites.rootsweb.com/~txrefugi/GillilandMassacre.htm https://www.rootsweb.com/~txrefugi/TealAnnieFagan.htm http://sites.rootsweb.com/~txrefugi/Fagancemetery.htm

-

2025/2026 Hunting Thread

It's a buddy's farm. He has a large operation and he leaves a few parts of fields/timber flooded to hunt. Wish I new of a resort to recommend. I'll ask him if he knows of anything around. I know he knows of a lot of hunting clubs around the area, but I think those are normally pretty private.

-

2025/2026 Hunting Thread

Drove on over to a friend's farm in Arkansas and met up with other friends for an extended waterfowl hunting weekend, last week. Had some very good hunts, there were generally 5-7 of us hunting at any one time. Ducks in the morning, goose one afternoon. Never limited out on ducks, but had a good action and a good mixed bag, mallards, pintails, gadwall, green winged teal, and wood ducks. Hunted some flooded fields and some flooded timber. We also got a good amount of snow geese and 4 specklebellys and one canadian. I spent about 4 hours cleaning them afterwards. I've already eaten all of the teal I got to take back with me. Will be having some sort of roast mallard this weekend. One friend took all of the snow geese to smoke and make into a pastrami like meat for all of us. It tastes surprisingly good when done that way.

-

Go Army, Beat Navy

The first test was relatively easy. During the second test, the power went out in the building (whatever the ME building was/is called) and we got to take home for the weekend to return Monday morning. I spent 17 hrs on that test and only got a 91. I wouldn't say easiest. Seems like it depends on who prof was.

-

2025/2026 Hunting Thread

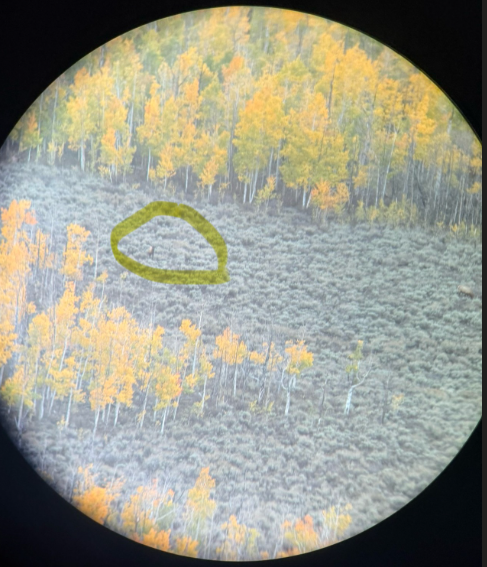

Went to Montana for an upland/waterfowl hunt with a friend who lives there, while trying to help other friends that had deer tags. It was warmer then normal and the pheasant weren't bunched up like we are accustomed to there, so I got fewer of them than I normally do. Got one grouse and a couple of Hungarian partridge. Saw some good whitetail bucks and one big mulie with a lot of smaller mulies. Got in one goose hunt the evening before flying back. Had to stop shooting at sunset, but the birds did not stop coming in to land. Only got Canadians, including one banded, but saw a ton (10,000+) of snows and specs about 30 miles north of where we ended up hunting. Wish I had more time. Buddy and his dog: Blind highlighted in yellow: On a side note, my dad got this on camera on a small piece of property in central Texas:

-

Surly Dad Thread

From the Jason Isbell's song Speed Trap Town referring to losing a big high school football game: "It's a boy's last dream and a man's first loss"

-

UT Language Website Fundraiser

bite de mulet?

-

Русский корабль - иди нахуй

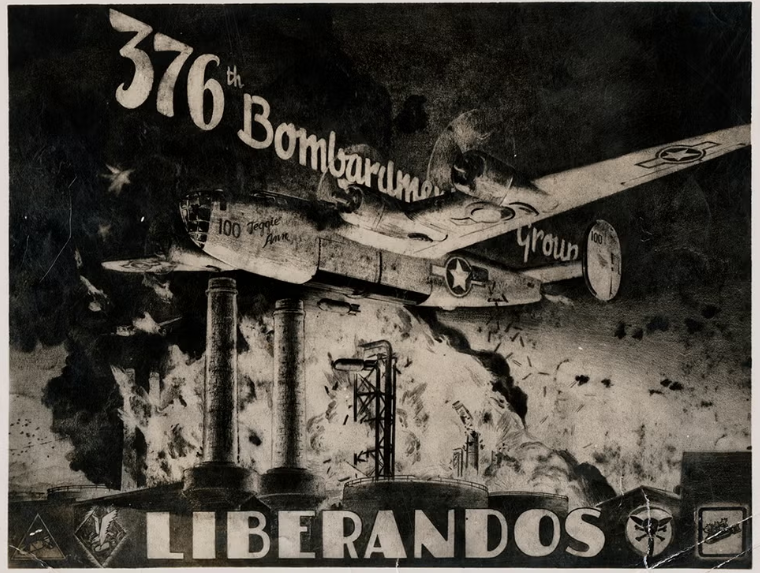

Sorry to continue the derail regarding B-24s, Ploesti, etc. I thought some might find it interesting that the 376th bomb group donated all of their records to the Briscoe Center at UT. I learned this researching my great-great uncle's plane. He was a tail gunner and was KIA over Budapest on July 2, 1944. https://briscoecenter.org/support/endowments/376th-endowed-internship/ Story from survivor of his plane: https://www.armyaircorps-376bg.com/kesler_earl_440702.html

-

2025/2026 Hunting Thread

-

It’s Time for Organized Resistance

So long, and thanks for all the fish?

-

The Leopards Eating Faces and Unlubed Dildo of Consequences Thread

I dated a French Tunisian girl. It was a lot of fun (also great food). Plus, she spoke four languages and was great fun and help to travel around. I remember her on the phone with her sister speaking French/Arabic, talking to me in English, then giving Spanish tourists directions in Spanish in Bordeaux all within about 30 seconds. She told me she learned Spanish by listening to Shakira while going to grad school in Mexico, of all things, and English by taking English lectured college classes in France. Agree that mixing of cultures is the best thing in the world and it has greatly influenced my life experiences for the better. Honestly can't imagine my life without it. Wish others would get with the fucking program.

-

2025/2026 Hunting Thread

Got back late last week from my 4th annual elk trip to a ranch in Utah which is basically an elk lease for a group of friends and I. Evening before opening morning we watched a nice 6x6 (see photo below) chase off a rag horn and spike away from his cows at about 600 yards. Bugling was crazy opening morning. Sounded like a bull every few hundred yards. Buddies got two nice 6x6s that morning in different drainages. I saw about 10 spikes and 20 cows and one nice bull that appeared just below the rising sun, so I couldn't find him in my scope. They mostly stopped bugling after opening morning. The next day, I ended up getting a smaller 4x5 with a Napoleon complex that was a 5x5 that had broken his main beam. I had already passed on a rag horn and spike earlier in the morning. The bull bugled at us from a thicket of aspen and sounded less than 100 yards away. After he bugled again we could tell what direction he was headed with his cows and ran around the corner of an old logging road and set up for him to cross from another old road. I saw him for all of 1-2 seconds when I pulled the trigger and he continued about 40 yards down hill into the canyon until he went down. The shot was about 95 yards. Interestingly, I shot this bull from almost the exact same spot I shot my bull last year. This year I shot close by down the road I was seated on as opposed to across the canyon. On the third day there was only one hunter remaining hunting for a bull. While he was far away in a heavily timbered canyon, we had a nice 6x6 with a couple of cows and a 4x4 with a bunch of cows walk near the cabin at distance between 150 and 500 yards. Wish I could stay out there longer. Great place to destress. Made a bunch of ossobuco over the weekend by cooking 3 of the 4 shanks. Been eating that all week.

-

The Leopards Eating Faces and Unlubed Dildo of Consequences Thread

-

Hegseth & the Boys

In Hegseth's video snippet on X or Bluesky posted earlier, he said "If you want a beard, you can join Special Forces."

Football ...

Basketball ...

Baseball ...

Other Sports ...

Futbol ...

🤫995🤫 ...

Gambling ...

Movies & TV ...

Music ...

Hobbies ...

Lulz ...

Food & Travel

...

Daily Texan ...

Business & Markets ...

Cloak Room ...

Help ...

For Sale ...

Board Discussion ...

Advertise...

Tailgate Donations